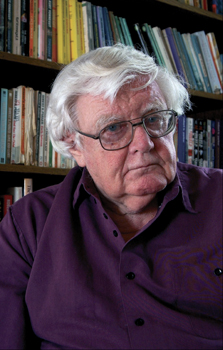

Albert Hunt

Director of Theatre and Complementary Studies

at the Regional College of Art, who later held the

fabulous title of Happenings Officer for Bradford & Ilkley Community College, Albert Hunt, was

employed between 1965 and 1985. Albert is the

author of Hopes for Great Happenings among

other titles.

“I came to head up Complimentary Studies on the proposed

Diploma in Art & Design course in May 1965. But we failed

to get the course and so frustrated, I found another job.

After lunch one day, I dreamt up a scheme and I wrote a

proposal setting out what I would have liked to have done

if I had stayed. I took this fantastic programme to the

Principal as a parting gesture and I was amazed when he

said ‘I don’t see why you shouldn’t do this.’ Because of

failure to get the course, I was completely free and for a few

years I did exactly what I wanted. They were good times.

“I came to head up Complimentary Studies on the proposed

Diploma in Art & Design course in May 1965. But we failed

to get the course and so frustrated, I found another job.

After lunch one day, I dreamt up a scheme and I wrote a

proposal setting out what I would have liked to have done

if I had stayed. I took this fantastic programme to the

Principal as a parting gesture and I was amazed when he

said ‘I don’t see why you shouldn’t do this.’ Because of

failure to get the course, I was completely free and for a few

years I did exactly what I wanted. They were good times.

Students were meant to spend 10% of their time on

Complimentary Studies but instead of attending weekly

classes we ran projects lasting a fortnight. This did not just

apply to Arts students but all students in College.”

Over the years, Albert was responsible for some incredible ‘happenings.’ For instance, in 1967, 300 students

commemorated the 50th anniversary of the Russian

revolution by re-enacting it on the streets of Bradford and

various public buildings, designated areas held by the

provisional government, were stormed by Bolsheviks.

“Another important project was The Survivors. I appealed

in the local paper for anyone who had lived through WWI

to come forward. We recorded their experiences and later

held an evening in a pub on Armistice night. People spoke

of the generation gap but long after closing time our young

students were talking to veterans.”

In 1968 this work led to Albert’s founding of The Bradford

Art College Theatre Group, which performed original and

provocative material to great acclaim at national and

international festivals. Vast amounts of research went

into devising these pieces. “For Looking Forward to 1942 (1970) we recorded the sincere beliefs of a number of

small fundamentalist sects and a spiritualist medium and

held a series of theatre workshops where we combined

the material gathered with history. The final show told the

history of WWII in the form of a Pentecostal meeting with

songs and opposing sides giving their testimonies.”

Other plays included: John Ford’s Cuban Missile Crisis (1971); James Harold Wilson Sinks the Bismark (1972);

The Fears and Miseries of Nixon’s Reich (1974) and The

Passion of Adolph Hitler (1975). Albert then spent 7 years

on sabbatical in Australia.

“I had written a book about Peter Brook and his phrase ‘necessary theatre’ stayed in my mind. We had done

my play, A Carnival for St Valentine’s Eve, about the

destruction of Dresden in London and Oxford before I went

to Australia. When I returned we took the show to Dresden,

then behind the Iron Curtain. One after another, young

communists in the audience denounced us until an old

woman spoke of her experiences the night Dresden was

bombed. Soon others joined in and there was an outpouring

of repressed memories. People later told us that their

children had seen the play and started asking questions. I

couldn’t think of any theatre more necessary than this.

There is now a distorted perception of the 1960s. I

passionately think the work we did, with people inside

and outside College, was hugely important. It was not

eccentricity but about engaging with people and valuing

their experiences. Having people cooped up in classrooms all

day, tested and harangued by authority, as they are today,

is true eccentricity.”

Photograph by Andy Vaines